Med Tech Talks

A father’s struggle inspires an epilepsy treatment system with Professor Mark Cook AO

Professor Cook has been profoundly inspired to undertake a career in neurology through witnessing his father’s struggles with epilepsy.

Through his internationally renowned research and the foundations of two med tech companies, Seer Medical and Epi-Minder, Professor Cook has made a tremendous impact in the treatment of epilepsy.

In this episode you will hear about:

More information:

Read Mark Cook’s biography : Professor Mark Cook AO

Take a look at the Epi-Minder website: Epi-Minder

Visit the Seer Medical website: Seer

Professor Mark Cook [00:01:48] Thanks for having me aboard.

Robert Klupacs [00:01:50] Mark, you have contributed so much to the field of neuroscience, particularly to combating epilepsy. And I know a little bit about this but, and I know our listeners don’t. So where did your interest in the field come from?

Professor Mark Cook [00:02:03] Well, you know, neurology is like a really interesting subject. Everyone’s interested in neuroscience, but I know I was really interested as a student, but I guess probably what had there are two things which made me do epilepsy. And one was the head of the department was interested in having an epilepsy service set up. So that was obviously very important. But I guess, you know, I’d been very profoundly influenced by watching my dad struggle with his epilepsy because, you know, it was clear that people had trouble managing it because they didn’t really know what was going on. He couldn’t really tell them because he often wasn’t aware of the seizures. And consequently he was on lots of medications and never achieved control and it was very disruptive to him. He had to stop working. He couldn’t drive it, obviously, you know, had a very profound impact on all of us. So I guess I was always interested in how you might do that better.

Robert Klupacs [00:02:52] First and foremost, you are a clinician and your patients come from as far as Sydney and all across Australia benefit from the epilepsy, the expertise that you and your team have in epilepsy treatment. But you’ve mentioned your father, but can you tell me more about what drove you to get so involved in research rather than just the clinical part of it and what problems you wanted to solve?

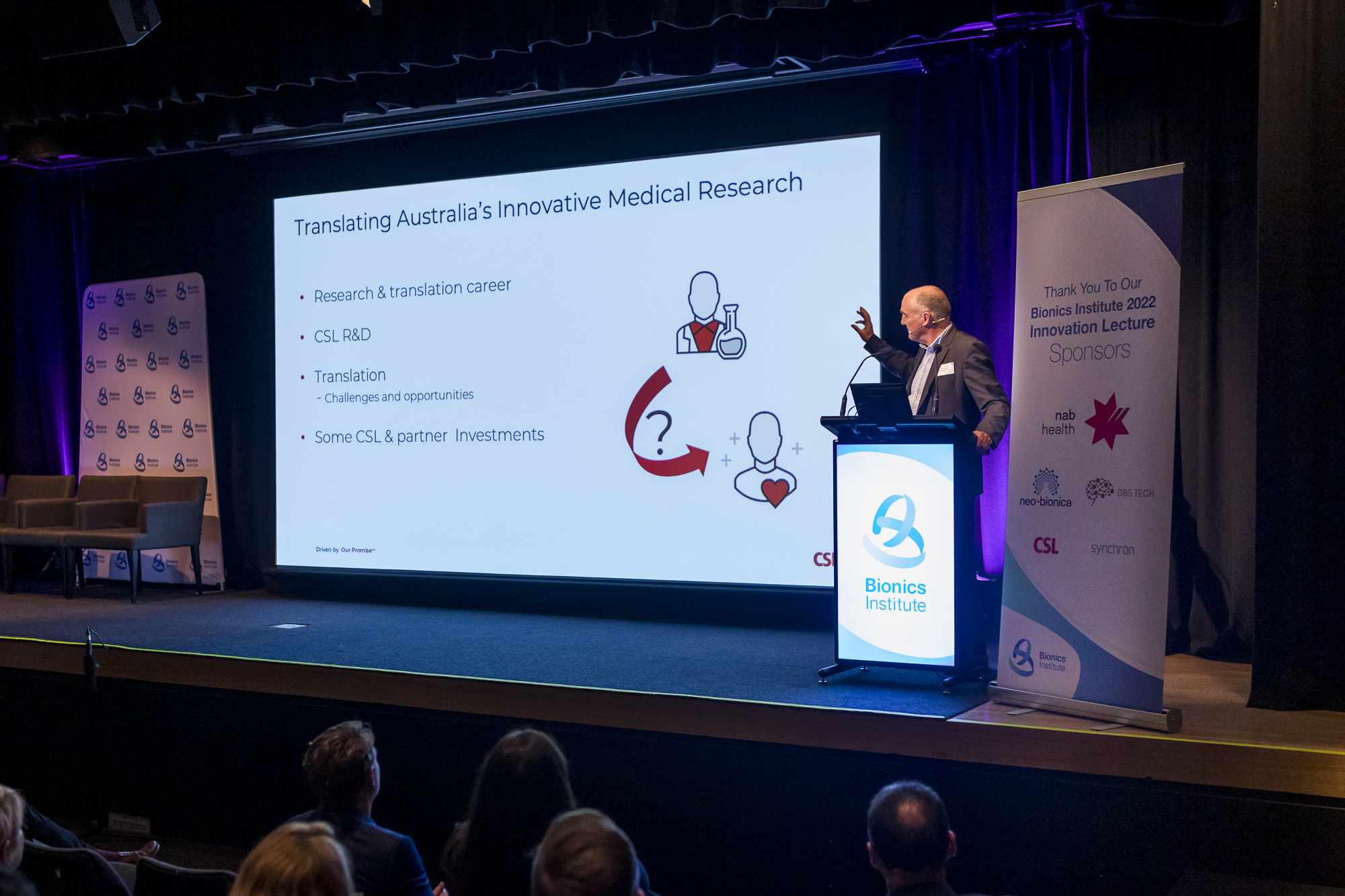

Professor Mark Cook [00:03:10] Sure. My early research interests were mainly around imaging because we needed to set up an epilepsy surgical service and new MRI technologies that were developing in the late eighties and early nineties were critical to that. So most of my research centred around that, but I became very interested in how you might predict seizures about that time. And, you know, the problems around protecting them were obvious. You know, the biggest problem was that you needed to have accurate records of a lot of seizures to be able to do it. They didn’t seem to be any easy way to do that, but I’d always wondered whether it could be done with an implantable device of some sort. About 20 years ago, Professor Graeme Clark, who developed the bionic ear, became involved with our department and showed me some of the technology that he was involved in and it was immediately apparent that we could modify this technology to do the sort of things I was interested in. We could use it to record seizures, and we could also use it potentially to stimulate the brain to stop seizures. So we became very interested in research around that and set up a collaboration with the Bionics Institute at the University of Melbourne to further this work and this led to us doing some first in human studies with another implantable device made by another company called NearVista, which was ultimately unsuccessful in the company, couldn’t achieve ongoing funding, but it did demonstrate that it was possible to implant devices that could continuously record EEG. And for the first time we recorded EEG over periods of months and years and were able to show that it was possible to predict seizures. But we also discovered that it might be that we could do it using a less invasive means. Now, that didn’t become clear until sometime after we finished the initial study because it was only through the analysis of the vast amounts of data that we’d acquired that this became apparent. But we realised that it would be possible to go back to our original plan of using a less invasive system based on the cochlear device and use that to record EEG continuously. And it took a long time, as you know, to get everyone on board with that plan. Fortunately, along the way, a lot of the technology in the background evolved dramatically which which made this possible. And I don’t think in retrospect that it would have been possible early on, but we didn’t realise that. And the reason it would have been possible is because we had no way to capture the vast amounts of data that come out of these or to analyse them in the timeframes that are required to provide that useful input. So a lot of things happened along the way. And you know, although I was very frustrated by how slow it all was, in fact, it probably worked to our advantage in the long run.

Robert Klupacs [00:05:37] You sort of you sort of touched on it because my next question was what led to the development of the Epi-Minder device and the related technologies. But and you sort of touched on it, but maybe you could just take it a bit deeper. So you’ve identified it. You thought you could do it, you had the pieces come together. But what was the seminal thing that changed in both entities? What happened? Who came into your life that you were able to look at me? I think there were other people I know that came into your life around the same time that allow certain things to happen. Can you just take us through that?

Professor Mark Cook [00:06:06] Well, there was people at the Bionics Institute who were very interested. Develop this apart from Graeme, of course, you know, there was Rob Shepherd, who was CEO at the time, and others who were very involved in the setting up with the bionics and people who’d come on board through our original engineering project with the hospital, university and the bionics who stayed on board. People like Dean Freestone and Alan Lai, who are who are still critical members of the team. And Dean and I went on with George Kennelly to to form Seer. Now the idea there was that having recognised that we needed to capture this data and stream it and then analyse it that we needed to develop a platform to do that and coincidentally almost we discovered that we had a viable diagnostic service along the way because some of the technology that we developed to enable that, let us expand it so that now that it’s become a diagnostic service available around Australia and and recently we’ve set up UK offices and we’ve got arrangements evolving now in the United States as well. But all of this sprang from that same arrangement and these same people, but I think integral to it was getting the engineers, the researchers, the clinicians in a room with the patients most critically and understanding what the problems were and what better solutions there might be to solving them.

Robert Klupacs [00:07:23] Yeah. And you know, Cochlear is a great company. We both love them, but they’re very conservative and they’re very focused. Can you just tell tell our listeners a little bit about the journey to get Graeme Clark 20 years before, who created the cochlear implant so they can get the company that makes them and sells them to get on board to help you make the minder device.

Professor Mark Cook [00:07:43] Well Cochlear we negotiated with very early around this plan to get access to their technology before in fact we’d started the first project and we started work with Cochlear on this concept and they became involved in forming a patent with it around us. And I guess, you know, a critical person to mention all this is Jim Patrick and Jim was CTO for Cochlear at the time and enormously supportive and helpful. You know, he was very interested in the project, could see the application and and what the opportunities might be around using some of the available technology that they’d developed. And so he was extremely helpful over the years, sort of making progress for us with Cochlear in developing the context. And I guess the next most important thing that came along was Yang Son and then, you know, Yang immediately saw the potential of the application and became very involved. And they were probably our first steps to making real headway in forming a how could I put it to, you know, a fixed commitment from from Cochlear, which and obviously, you know, they’ve been they’ve been so important all along the way. And as I said, the technologies that they developed that, you know, became available to us through that, particularly the ability to stream the data from the Bluetooth unit behind the ear, which collects the data from the implant. I mean, that changed everything. I mean, if we hadn’t had that, we would have been back in, you know, the technology of ten, 15 years ago transferring SD cards from devices to computers, which is pretty much what we did with the first studies.

Robert Klupacs [00:09:22] So, you know, I’m biased. I think the Minder device is a fabulous innovation and I think we all agree has the potential to make a huge impact on the treatment of epilepsy. But for our for our listeners can you paint a picture of the difference device can make to the life of a person with epilepsy. And you know, you and I have known each other now for six years, and you’ve told me a lot about what it is and most the general public don’t know much about what it is to suffer from epilepsy and perhaps for our listeners, it’d be great to for you to give an insight into what you think the device can do and perhaps what the life of an epileptic patient actually is.

Professor Mark Cook [00:09:58] Yep. So. So epilepsy. And it consists of brief epilepsy. Sorry. Epilepsy consists of brief electrical discharges in the brain, which usually start in one area and might spread. I guess when people think about epilepsy, they think of people with lots of other disabilities, but most people with epilepsy don’t have any other disabilities. Anything that injures the surface of the brain, however tiny, can cause seizures and some genetic problems can cause epilepsy as well. And most people with epilepsy are perfectly well in all other regards. The other big misconception about epilepsy is that people collapse and convulse with their seizures, and that’s not so common in adults. They can have them, and that’s often what brings them to attention. And some people only ever have them. But most people with epilepsy have brief episodes where they lose contact with the environment, which perhaps doesn’t sound so serious, but it is when you’re driving a car or doing something at work that might be dangerous. And in many parts of day to day life, taking care of children, for instance, crossing a road, you can see that if you went off the air for a minute or two at a time and you had no awareness of that, that would potentially be very hazardous. And it is. So it’s a big problem as well. There are other problems associated with epilepsy which can affect people’s memory and there’s a risk of death with the seizures as well as accidents. We don’t understand the mechanism of this very well, but there’s there’s lots of hazards with the seizures themselves and of course, the treatment. So many people find the treatment more burdensome than the condition because the treatment itself might slow up their thinking or have other unwanted side effects on other parts of their body. So it’s a big problem. Now, what complicates the whole thing is that people often don’t know when they’re having seizures, so they might think they know or they might be reporting events that they think are seizures, which are not, or they might just not recognise they’re having seizures at all. And that’s really common. And again, with, with the ambulatory monitoring system where we capture data from people at home, we knew this from hospital, but we can see it on a massive scale, recording people in their home environment that people are often completely unaware of their seizures. They might be reporting events which are only not seizures and not recognising any of their seizures or any combination of the above. And amazingly and this is another remarkable thing about doing it at home, even when they’re with other people who are close to them, perhaps, and understand what they’re looking for, they still often don’t see the seizures and recognise them. And if you can imagine as a neurologist seeing patients and you’re trying to adjust their treatment according to what they’re telling you about the seizures, and they really don’t have any idea. It’s it’s kind of an impossible situation. And you can see why epilepsy is such a difficult problem to control because we don’t really have any idea what’s going on. So with the device, we hope to fix it. We can actually record seizure activity very accurately. We can see when and where it’s happening, what time of day. And not only does that, it let us count them accurately, which by itself would be a very significant achievement because it would let us tune treatment according to what’s actually happening, rather than the guesswork that it currently is at the moment. But as well, once we’ve got that information, we can do other smart things. We can see the effects of the therapy, we can use it to forecast seizures, much like a weather forecast. And I mentioned before that we learnt from our earlier implantable device study that it was possible to do this once we had been able to collect a sufficient number of seizures and seen the pattern and these complex patterns of seizure activity that underlie them allow us to forecast them often with a great deal of accuracy for individual patients, but it’s different for everyone. So you need to record each person’s particular. A pattern of seizures. We expect there’ll be many other uses so that, for instance, there’s a close relationship between sleep and epilepsy. We can measure sleep with the device and we can understand the relationships between people’s seizures in their sleep. And we can probably use it to help us define patients who are suitable for surgery in a various group of techniques, looking at where the seizures are coming from and how often and so on. So there’s potentially lots we can do with the implant.

Robert Klupacs [00:13:52] So Mark and everyone thinks that if you as a clinician, a serious man, but I understand you have a lot of other interests and I understand music is a passion of yours. Can you tell me a bit about who you like and how eclectic your tastes are?

Professor Mark Cook [00:14:05] Thanks, Rob. I’d love to talk about music forever to everyone, and as a lot of people know, I love torturing people with YouTube nights over perhaps some alcohol. And and these will involve my my favourite topics of late seventies early eighties inner city Melbourne punk, which is my area of special interest. And more recently of course, you know, I’ve been still very interested in various other thrash and punk bands and including the latest crop and frequently go out and see them with various acquaintances, both from bionics and other locations around Melbourne. And you know, you soon find that you’ve got a dense network of colleagues throughout the university and the hospital who have similar interests in your music once it’s out there. So, so I did go through a period, I’ve got to admit, where I was very into Seventies Funk and I enjoyed that. But that did stop a lot of people from coming and visiting me. Robert Klupacs [00:15:02] I can understand, really can understand that. So I understand you really have a big, big fascination and interest in someone I like a lot: Nick Cave.

Professor Mark Cook [00:15:12] Yes. So so I’ve been seeing Nick Cave since 1979, maybe, maybe 78 boys next door, as a matter of fact. So, uh, and I can remember the first show I went to in the, uh, well, it’s actually above the, you know, where the swimming pool is at Melbourne University. So there’s a roomup there, which I think is a gym now, but that was actually a venue where bands would occasionally play once upon a time. So the first place I saw I’m still got the posters for that event and, and yeah, and then I used to see them in the in the years that follow regular at least twice a week at various places around around town hearts was a very prominent, just off Nicholson Street in in Fitzroy there but other bands from that period who’d often play with them. You know I still enjoy very much the primitive calculators and and other obscure in the Melbourne bands of the time too that fit through the door. Flintstones, Meet the Flintstones.

Robert Klupacs [00:16:12] Did you know all the members of TISM?

Professor Mark Cook [00:16:14] No. Well, I mean, it’s hard to right?. Yeah.

Robert Klupacs [00:16:17] It’s. So you have an interest. Do you actually play.

Professor Mark Cook [00:16:21] Only any electronic devices called computers and CD players?

Robert Klupacs [00:16:29] So is this is this something that, you know, young budding entrepreneurs or neurologists need to need to follow and and channel? Do they need to follow through?

Professor Mark Cook [00:16:38] I think it’s absolutely essential.

Robert Klupacs [00:16:40] It’s awesome. Really. Is the other company you’ve been involved with See rMedical? It’s been a truly unbelievable company. It’s I think at last call, I understand it’s got 250 people working there and it’s made a huge mark in the Australian and now international med tech industry. Can you just give the listeners some of the background and some of the secrets behind Seer’s success in such a short timeframe? Because I understand it was only launched in 2017/18, now 2022 is now a world leader in space.

Professor Mark Cook [00:17:12] The trial will be approaching our 11,000 patient monitoring study shortly. So so we’ve done a lot over that period. And obviously, you know, Dean with his engineering skills and George with her organisation and financial skills and insights into how to arrange all of this are obviously key components of it that, you know, we needed to set up a system so we could catch data that was being streamed from devices to the cloud to so that it could be analysed constantly by machine learning systems. Because, you know, again, what we discovered from the earlier study was if someone had to sit down and actually look at this data, it was never going to happen because there are vast amounts of data and it takes you almost as long to read as to acquire it if you do it using humans. So it needed an automated system. So we set about system of capturing it so we could figure out how to do that. And we wanted lots of data, so we figured we’d do it on patients who we studied at home, because in hospitals, very expensive. It costs $15-20,000 for a week of monitoring and patients and beds are very limited. So there’s probably less than 50 beds Australia wide. So collecting this data is very difficult on the scale that we need it because we needed thousands or tens of thousands of hours of recording at least so. We we set up this system where we send people home with a recording device on their scalp. And as I said, the big problem was keeping the electrodes on for more than a couple of days. So home monitoring, where we send people home, the electrodes really hasn’t been done on any scale because you can’t keep the electrodes on. But Dean devised a way by which we could do this, and so we were able to collect data for up to a week. If you can collect data for a week, then you’ve got, you know, a diagnostic process which could replace an inpatient hospital stay, which it pretty much has. So at the moment we record, say, up to 120 patients a week, which obviously is more than double the national capacity for monitoring in any one week. And the insights provided through it, very dramatic, because for the first time, really, any neurologist can order this and find out what’s actually happening with seizures. Now, the time frame still much shorter than we’re talking about with an implantable device, but even in a week, you might be able to make the diagnosis for sure. That’s often a big challenge at the start. You might be able to see whether the symptoms the patients are complaining of are actually seizures, and you might be able to understand what the effects of those seizures are on their day to day life. And so it’s been really dramatic. It’s it’s very different from inpatient monitoring, which I’ve been doing for the last 30 years. A patient stuck in a bed. You’ve got a camera on them and you’re watching them 24 hours a day. It’s a very artificial environment. You often see events which are pretty dissimilar to what they’re getting out of hospital because we often deprive people of sleep and stop the medications to try and provoke the seizures. And that changes their character. But as well, in the home, you see a lot more about what actually happens to the patient with them. And you come to appreciate those sorts of situations where, you know, the patient is with other people in their family. We’re very close to them. Sometimes sitting around a kitchen table talking and I can see they’re having a seizure, not just on the EEG, but I can see it on the video. And yet it’s apparent that no one else in the room appreciates it. And it is sometimes quite startling. And, you know, I used to think that when patients came along and said to me that they had a seizure in sleep and their partner didn’t notice it overnight, I said, well, it could have been a major seizure because they would have noticed that for sure. But I don’t believe that anymore. Some of the things you see in the ambulatory setting are quite remarkable. So it has changed practise. And you know, at a conference here recently, it really cheered me that neurologists were coming up and told me, you know, this, this it just completely changed their whole practise, how they manage patients snd that’s incredibly satisfying.

Robert Klupacs [00:20:49] Maybe that’s part of the answer to my next question, because, you know, your your career, as you said, 30 years, probably a little bit longer. You’re nearly a year older than me at least.

Professor Mark Cook [00:20:58] So you might think so.

Robert Klupacs [00:20:59] Yeah. It’s like looking back, your career has been stellar and spent several decades, shall we say. I mean, you’ve just talked about some of the highlights, but what are the highlights when you’re looking back now, you know, of your career, what would you say the highlights have been? What have you learnt in your career that people new to the field will find useful? And knowing what you know now, what would you do differently?

Professor Mark Cook [00:21:23] So I’ll start with the last one. So probably I don’t think I’d do anything differently in terms of what I chose to do and, you know, I guess I’d still do neurology again and I’d still do epilepsy if I if I had my time over again. And I guess what would have been. What we’re really useful things to me along the way. One and this came when I was working in London that my research assistant was an electrical engineer. And I think, you know, something we don’t appreciate in medicine is is what exactly it is that engineers do. And that was a big eye opener and what they could do. And and also the different ways of approaching problems that people from other areas of science could could bring. And, you know, the engineers were quite remarkable in that regard. So that was a huge insight for me, that and the importance of being able to translate these into something commercial. Because, you know, over the time I’ve seen a lot of very interesting research projects which ultimately don’t lead anywhere because there’s no clear path to commercialisation. And unfortunately, there’s a culture often in medicine that this is dismissed as somehow the wrong way to approach problems. But of course, you know, if it’s if someone’s not prepared to fund this somehow, it’s never going to work for anyone. And people don’t seem to grasp that. So I guess other big turning points for me were understanding the reimbursement, regulatory and investment side of things, and much of them came to me initially through involvement with Bionics Institute. And, you know, in our attempts to get funding early on. So I think, you know, learning that you have to get your ideas out there, speak to a lot of people and you and I have done an enormous amount of that. But, you know, some huge opportunities arose simply through just being out in the field, giving talks to groups of people that perhaps at the time didn’t think were going to be relevant to you, but but turned out to be incredibly important because just one person can make all of the difference. You just need to get one person’s interest. So getting out there, pitching your story and tuning it and having a team, and I guess that would be the other important thing, you know, finding out the importance not just to you and making things happen and your patients and all that, but if these things are going to work, you’ve got to have a strong team who ideally have stuck together over a long time and and understand one another well and get on. So so I’d say that was the other really important thing, but also that, you know, you need to keep good relations with a lot of people that you need in your life. And it might not be apparent to you at the time that they’ll help you develop these things and some people’s skills. And apparently, again, as with the engineers, you know, I think we often make this error in medicine that, you know, when you talk about reimbursement and regulatory people, you imagine they’re just some sort of bureaucrats. But the skill and expertise involved in these areas is immense. And, you know, we don’t even know what we don’t know and from the medical perspective.

Robert Klupacs [00:24:27] It’s back to the first question. So you’ve done so many things, you know, what would be your highlights?

Professor Mark Cook [00:24:33] Yeah, so highlights. So I think, you know, one thing that the one thing that was a real highlight for me was early on with the imaging, you know, recognising that we could measure very accurately small parts of the brain and that this was sufficient to define areas that could be removed surgically with very good results. That was really exciting and it worked and it allowed us to sit up, you know, at the time was a very low cost epilepsy surgery unit. So it was a big insight. It was gaining a bit of a of understanding about how we might apply maths and engineering principles to understanding complex imaging problems, which actually led directly to the relationship with epilepsy prediction because they’re similar sorts of the analytics involved and similar people who were skilled in that. And I think the recognition that their patterns to seizure activity and whilst people said to me that time everyone knows that there are patterns associated with seizures, I don’t think we really understood that. Some people thought that there were seizures associated with the menstrual cycle and so on, but it was much deeper than that. And I guess, you know, when we had hold of data that we’d got from your wrist or I was able to show something which I’d been interested in for a long time, interest improving for a long time, and that was that there were underlying patterns that we could formally define using, using mathematical principles and show that individual patients had complex cycles of seizure activity. And being able to do that was very exciting. Did took me a very long time to get it published.

Robert Klupacs [00:26:05] Just going to change take a little bit back to the innovation. So I say you are now one of Australia’s great innovators and in this whole series which is trying to tease out from people what that means to them, because everyone has a different view about what innovation actually is. But from your perspective, how do you define innovation know?

Professor Mark Cook [00:26:23] Can I go back to the other question and because probably I finish there on the scientific bits, I was going to say that, you know, other real life highlights, though, we’re of course, you know, the work around our invasive systems and sort of our implantable systems and. You know, the NeoVista, which was an invasive implantable system and the remarkable insights it provided to epilepsy. I mean, that was just spectacular. And, you know, I think I could honestly say it’s changed a lot of people’s view of epilepsy and neurology. And but, of course, you know, along the way with the modern device, people have often said to me, oh, that must be very exciting to get this, but and very excited to get Cochlear on board. And it was all those things were great. But by then it’s been going on so long, you know, you’re sort of a bit fatigued and it was great to get them. But the really exciting bit was seeing that first data come off the device and seeing the actual EEG come off the system. And my initial thought would be that I’d be sitting around with the people from Cochlear and and open to saying, Well, look, I know it doesn’t look much to you, but believe me, we can make something of this. And in fact, what we saw was beautiful EEG and we could see the seizures very clearly. And and that was just, you know, just so exciting.

Robert Klupacs [00:27:34] I do remember I was there with you and we were pretty excited .

Professor Mark Cook [00:27:40] Yeah. So so back to the innovation. Well, I think innovation. So a lot of people have ideas and you know, people are often frustrated that they’ve had ideas and they can’t make them happen. And I guess to me, the innovation part relates not only to having the ideas, but being able to gather together the people or the organisations or the structures that you need to make it happen. And I think the opportunity that I’ve had being at St Vincent’s and then, you know, the association with the Bionics Institute in the universities, I’ve had access to these remarkable people who have these skills and if they haven’t had them, we’ve been able together to go and get people who’ve had the necessary skills, as I mentioned, around be reimbursement and regulatory or whatever or running clinical trials. So we’ve been able to do that. So I think innovation is as much about being able to understand what the problem is and how you need to approach it and how you need to gather the right skills to make it happen. Because unfortunately, lots of people have good ideas that never come to anything. It takes a little bit more than that. Yeah.

Robert Klupacs [00:28:46] It’s it’s a good insight because it following on from that. So you’ve spent a lot of time working with groups around the world over your career. what do what does Australia do well in terms of that, you know, innovation maybe the next stage and what could we learn better from other people? And you’ve seen other people do it

Professor Mark Cook [00:29:05] I think we do it pretty well here and I think, you know, we have some unique opportunities because the culture of Australia is conducive to clinical trials. I think, you know, the general population understand what we’re trying to achieve and they accept that, you know, the objectives are often pretty ill defined and that we might get where we want, but there’s no way to figure it out other than to try it. And as long as everyone understands that and understands the risks involved and of course, with medical devices a bit different than with the medication, I mean, the medications can be very dangerous to potentially, but usually they’re not devices. You know, I mean, generally we’re working from understood principles, but still it involves surgical procedures. And, you know, there was a bit more hazard for the patients. But again, if everyone understands that and I think the population here do, I think the the the government understand that. I think hospitals understand it. And I think the public hospitals increasingly over the last ten, 20 years especially, have come to understand that it is actually a part of what they need to be doing. So clinical trials more generally and devising new technologies and participating in in making new treatments is really one of their measurable outcomes. And I think government are very interested in that too. And of course they’ve got a commercial and industrial component to their interest. But nevertheless I think that helps us here in a way which is very difficult elsewhere, either because the community is not quite as receptive or the regulatory authorities. And I think this is a big problem in a lot of countries that the regulatory authorities are not quite so open to these opportunities and that that really does slow things up very dramatically. On the downside, we don’t have a well, perhaps we do have access to the amount of financial resourcing that we need. But again, we’re so poorly skilled in the area and we understand so little of it. When I when I speak to my, you know, North American colleagues particularly, but certainly the Europeans, too, they’ve a much deeper understanding of of how these things are structured and how you might need to develop the necessary funding streams to support them. Here. We’re very dependent on the idea this is all going to come from the, you know, HMRC or ours or other large government funding bodies, which is a great way. And obviously we started off with some of this funding too. Great way to get going. Probably not the best way to keep it going then.

Robert Klupacs [00:31:32] So just in this series, one of the things we’re trying to tease out is the role and need for mentors, for innovators. I know you’ve mentored many people. Myself included. But who was some of the people that led you on the path that you’re onto tonight? You mentioned Graham Clark, clearly, but I know there’s others.

Professor Mark Cook [00:31:49] That would have said you mentored me, Rob

Robert Klupacs [00:31:52] No, no, no. I learnt everything you can imagine, you know, that.

Professor Mark Cook [00:31:55] I would say, you know, a very important person to me was, you know, probably the first neurologist that I worked for in Cambridge to stand to was very influential because he was open to everything and encouraged me just to do things I was interested in, but really, really important. Was Ed Byrne who you know, was who became the head of neurology at St Vincents, just when I was a student, and then later I worked for him as a resident and a registrar and then later as a as a colleague. And I still have very close involvement with Ed . And Ed was incredibly supportive and, and helped facilitate a lot of these connections, including with Jim Patrick originally, as a matter of fact, from Cochlear. And and Ed was involved with Cochlear to a degree to which which assisted that. But but it was incredibly influential. And then then later Graeme Clarke was, who was also very important, obviously, and was similarly clearly very excited about the opportunities available to improve and use differently the device that he’d had for quite a different purpose. And that obviously got him got he’s got his interest up and but he’s always been so very positive and so useful making contacts and pointed to the relevant people. So they’d probably be the most the most relevant mentors that I’ve had.

Robert Klupacs [00:33:13] From your perspective, what do you think the biggest threat and the biggest opportunity in med tech in Australia and perhaps even the world is at the moment.

Professor Mark Cook [00:33:22] Well, right now this might become dated very quickly, but when people are listening to this podcast, but the current financial crisis is obviously a really big problem because, you know, things of a very abruptly, you know, over a matter of weeks, dried up medical technology funding and, you know, the problems there are obvious. So those sorts of problems pop up periodically, obviously. And they’re they’re very significant issues outside that. I would say the biggest obstacles are the problems still. I mean, I’ve spoken about how conducive the environment is here, but the speed at which you can get processes through ethics committee and the regulatory authorities are still big problems, chiefly because, you know, they sit up more or less to deal with with pharma. And pharma are usually coming from a background of big companies and, you know, they’ve not got limitless resources, but, you know, they’ve got a longer time frame and, you know, more flexibility than you do if you have a Start-Up medical device company where as with the COVID situation recently, if you can’t do implants for nearly two years and you’re funding that, then you’ve got a very big problem on your hands and perhaps that’s a terminal problem. So it’s been catastrophic in that sense. The COVID situation is, but generally, you know, trying to get things through ethics committees and timeframes where they often don’t understand that the process delay of a couple of months might be, you know, the end of the project.

Robert Klupacs [00:34:49] From your perspective, I know you’ve had some quite interesting discussions with various people over the last few years, including me. But what do you think should be done to increase translation and commercialisation of research of Australian innovation.

Professor Mark Cook [00:35:02] I guess in. Again to improve it, we need to. I mean, all of this comes out of universities and and hospitals and a lot of the original ideas do anyway that let you get things rolling. And, you know, I’ve said already that there’s perhaps a bit of a misapprehension that because you’ve had the idea that, you know, you end it all completely. And I think that that problem afflicts often universities and hospitals who believe they should own it all. And I don’t think they understand how this stifles innovation because especially at universities, you know, the culture certainly in Australia isn’t conducive to clinician researchers getting into the business side of things, particularly it isn’t structured to allow people to take off the necessary time. And I think, you know, most of the people in universities and hospitals have no idea what this actually involves. And so they don’t appreciate the commitment that it requires on the part of the people driving it in terms of their time and trying to find an income over that time as well. So I think that’s a really big obstacle. So in my view, the arrangements around ownership of IP because if you can’t go out as, you know, the lead of a Start-Up and tell people that you own the technology, then you’re really behind the eight ball and whatever universities and hospitals and other large organisations think. It’s a huge turnoff for the people that you interact with. And you know, I can I can tell lots of stories about that, but putting a card with the university logo on the table when you’re meeting with a venture capitalist and seeing them recoil is quite a startling experience. And, you know, and because a lot of will just say that’s too hard at that point. So we need to open the environment up very dramatically. And we are seeing that. I mean, universities are appreciating that now and we’re seeing great stuff at Melbourne with Duncan Maskell and and other universities are taking the same long way. They’re realising that they need investment funds, they need to have some ability to be flexible with arrangements around research, around ownership, and they need to set up suitable structures to allow them to develop that. And that’s true of hospitals as well. I would say that, you know, many know that I’ve complained about this. I have found the process somewhat adversarial, shall we say, in negotiating with employers around these sort of matters. And I think that’s really unfortunate because, you know, this is something which can work for everyone if everyone facilitates it. And, you know, that’s been a really hard that to get done.

Robert Klupacs [00:37:44] Last question and this is from some of the listeners have asked me about who know you quite well. And for people who don’t know Mark, when you Google him, you’ll see a very handsome, debonair man with short hair. But quite a few people have now asked me in recent times since COVID, your hair is grown very long and many have asked me to ask you, when are you going to get a cut?

Professor Mark Cook [00:38:05] Well, I have had I had a cut a few times, as a matter of fact. So it would be longer. You can reassure that because, you know, I didn’t want to embarrass everyone too much. But no, unfortunately, it’s a side effect of COVID lockdown consequence.

Robert Klupacs [00:38:18] So thank you, Mark. There’s a lot of more questions I could have asked you, but we all got limited time. So I’m going to thank you for your time and you’re going to sign off because we’re so privileged to have worked personally. I’m so privileged to work so closely with you. In my time at Bionics Institute, I’ve learnt a hell of a lot about how to work through some of those interesting discussions that you’ve had. You seem to be one of the few people I know that can keep everybody happy. It’s a great gift.

Professor Mark Cook [00:38:43] I’m glad it appears that way, but what can I say?

Robert Klupacs [00:38:50] I think you can. And we really thank you today for imparting some of the knowledge and experience to our listeners. I thank you for giving us your time and know how valuable it is, particularly in your busy schedule. You’re involved in two companies you’re still doing clinic. You’re still seeing patients. So I know time is valuable, so thank you for giving it to us today. I am extremely excited to follow the journey of minder and Seer and other things. I still think you’ve got a to do and we’ll be watching it very closely for our listeners. I hope you enjoy listening today and I look forward to introduce you to other guests in future podcasts. There are links to everything we talked about in the show notes and we look forward to welcoming you next time.

Listen to other episodes of Med Tech Talks here